In the late 1960s, Gary Courneya and David Bradley Fuller were introduced by a mutual friend. Fuller had been running a small fiberglass design company, and Courneya had earlier been in sales in Beverly Hills, California. The two partnered in a business, Gary’s Bug Shop, which produced parts and kits for the dune buggy market. Fuller designed the bodies, and Courneya handled sales.

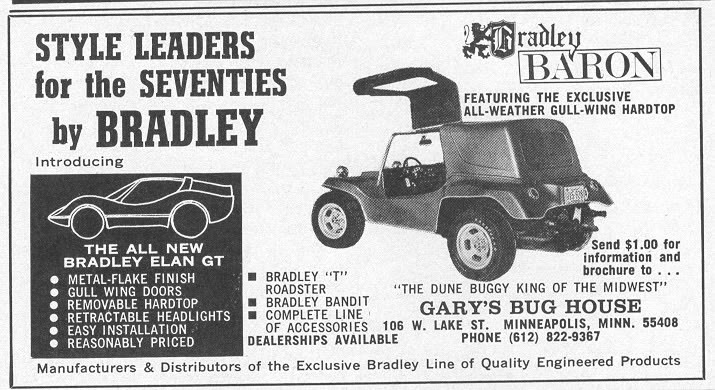

Period advertising copy for Gary’s Bug Shop lists a variety of different models already bearing the Bradley name, including the Bradley “T” Roadster, the Bradley Bandit and the Bradley Baron. This last model was a dune buggy with a hardtop and gull wing side panels. Also mentioned was a forthcoming Bradley Elan GT.

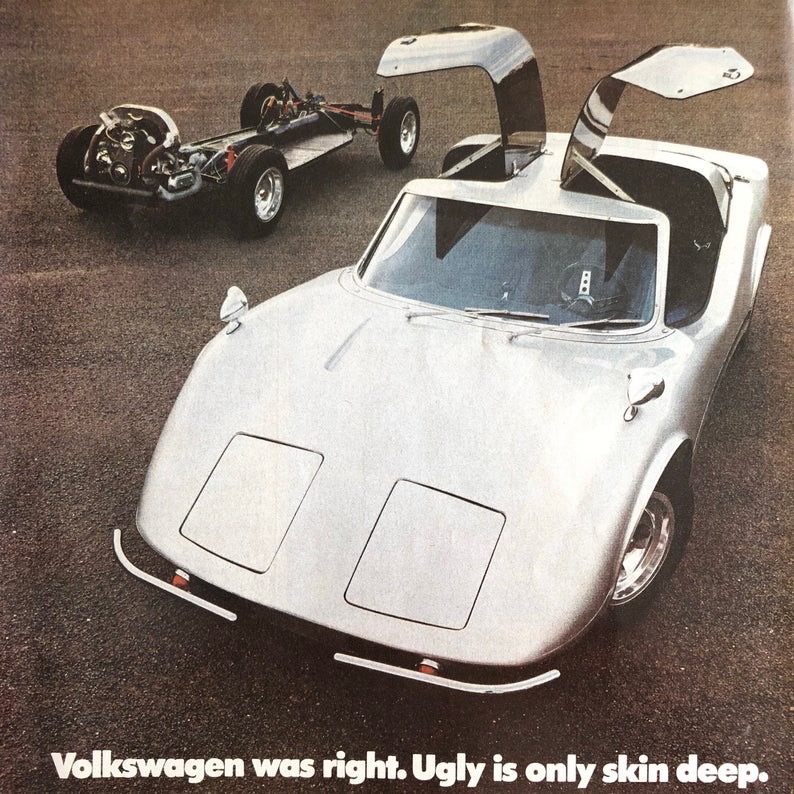

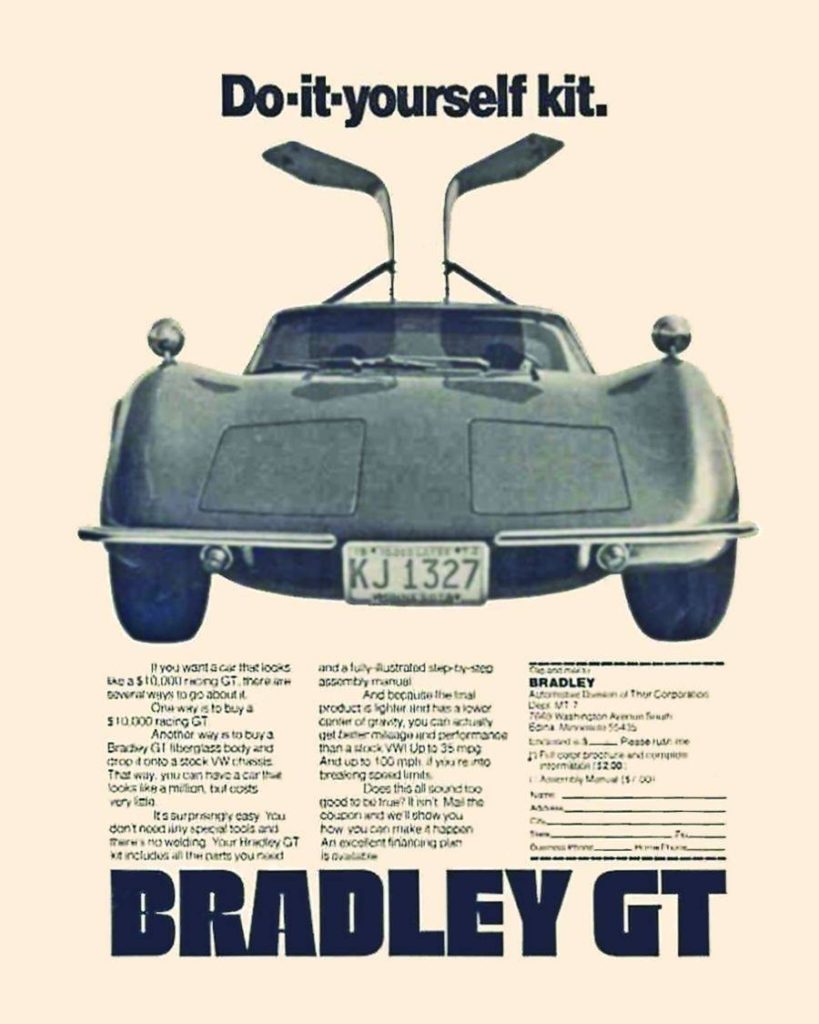

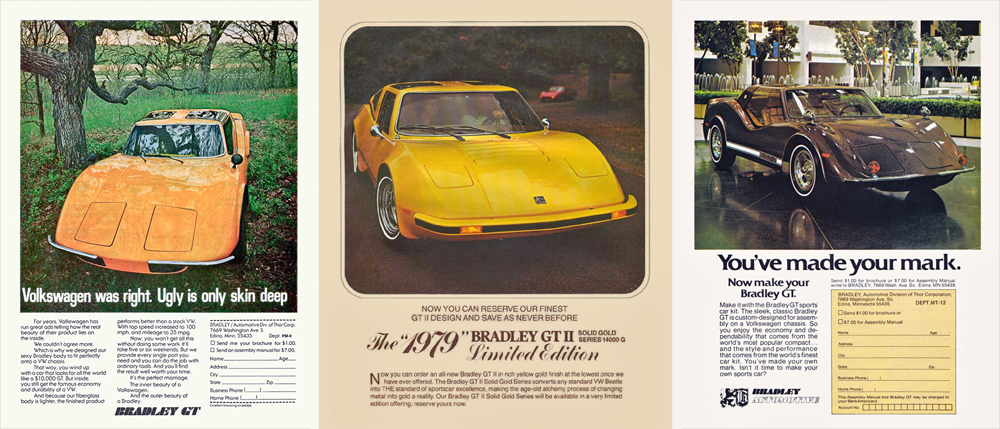

Bradley Automotive began selling their first product, the Bradley GT, in 1970. Like the earlier products of Gary’s Bug Shop, the car was built on the chassis of the original Volkswagen Beetle. Interest in the new GT was generated by advertising widely in a broad range of popular magazines. Anyone wanting more information was asked to send US$1 to the company for a brochure. When this promotion began, neither the brochures nor car existed.

The partners raised capital by offering 80,000 shares in the new company for sale at US$1 each. Half of the shares were quickly bought by the vice-president of a local construction firm, while the balance was sold over the next six months.

To accelerate sales, Courneya began telephoning sales leads obtained from the write-ins directly. During these calls he also began using the name “Gary Bradley”, a fictional character whose name was the combination of Courneya’s first name and Fuller’s middle name. The fictive “Gary Bradley” was even referred to as the company’s founder and president, and his signature appeared on some company legal documents. Appearances by “Gary Bradley” were actually Courneya.

By 1973, the company was in need of another infusion of capital. One of the original investors agreed to put another US$90,000 into the company on the condition that a professional manager be brought in and Courneya move to sales full-time. After this restructuring another US$250,000 was made available to them from Community Investment Enterprises, Inc, (CIE). Courneya and Fuller were able to repay their investors and buy out smaller shareholders as profits began to grow. Courneya was re-appointed president. In the early 1970s, the Bradley ads began to describe the company as the Automotive division of the Thor Corporation.

By 1977 the company’s sales had grown to a six-figure net profit from roughly US$6,000,000 in sales. New offices were obtained in Shelard Plaza, and the company was featured in an enthusiastic article in the local newspaper. The company introduced the Bradley GT II, a new, much more refined vehicle that year.

Between 1977 and 1979 Fuller left Bradley and established another company named Autocraft Inc., which became a supplier of bodies to his former company. Bradley would eventually contract out all of their manufacturing, not producing any components themselves.

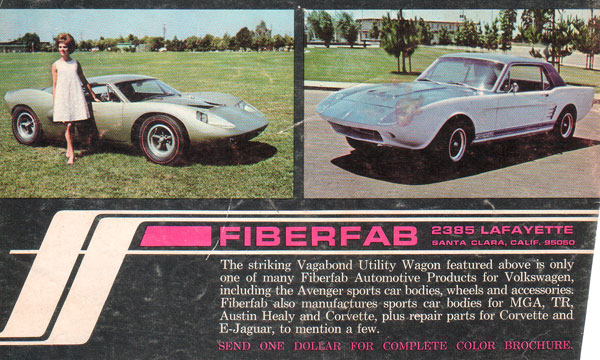

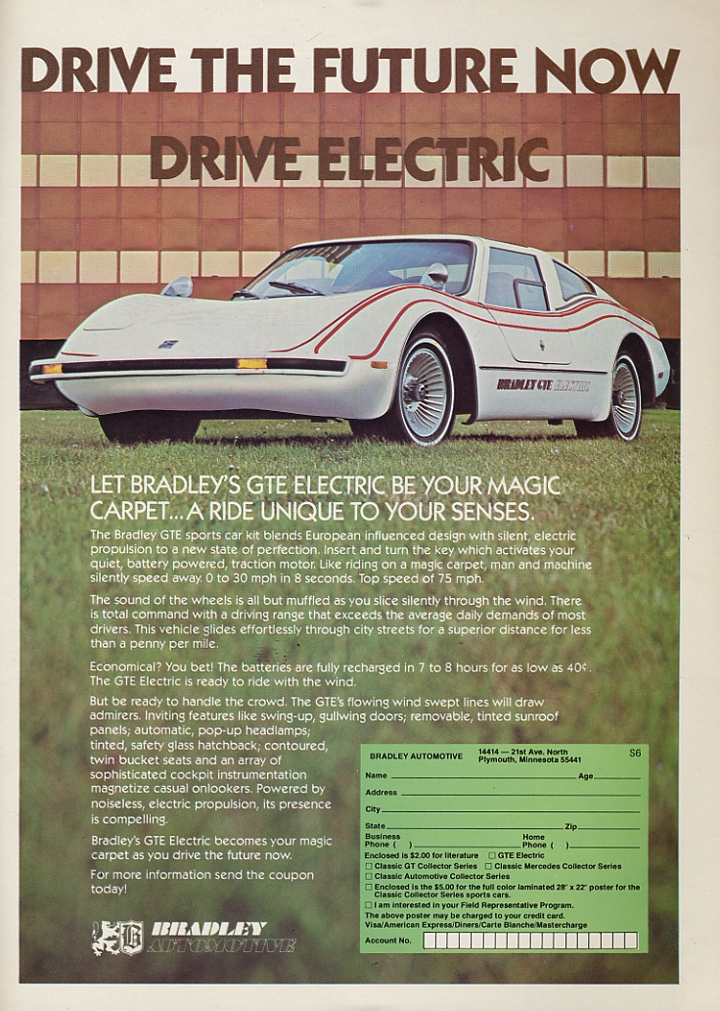

In 1978 seven of Bradley’s salesmen defected to their competitor Fiberfab. Bradley sought an injunction preventing the competition from enticing any more of their sales staff to leave. Courneya claimed that the company experienced a loss of $300,000 in expected sales in October of that year. Bradley filed for bankruptcy shortly thereafter and operated under Chapter 11 protection until April 1980. Six months later the name of the company was changed to Classic Electric Car Corporation. The name change reflected a plan to sell an electrified version of the GT II. The company underwent another name change, this time to The Electric Vehicle Corporation (EVC), some time later.

Complaints and lawsuits from dissatisfied customers began to mount, and picket lines appeared outside their head offices. In 1979 the Minnesota attorney general’s office asked for an injunction that would force EVC to warn its customers in writing that the company had either shipped product late or failed to ship it at all. At the end of July 1981 the attorney general formally charged EVC with consumer fraud.

Reported deficiencies included kits that arrived missing key parts, or parts that did not fit. Some clients did not receive their kits at all, as the company was taking orders for 30 to 40 cars per month but only had the capacity to produce 10 or 11 kits in that time. Another major issue was Bradley’s “Executive Broker Program”, which claimed to offer prospective buyers the chance for significant income. The buyer was offered a discounted price for their kit and the exclusive right to be the licensed Bradley broker for their geographic area. It was discovered that every kit buyer got the special pricing, and that other “dealerships” were in the same area.

Named in the attorney general’s complaint were Courneya and Deil Gustafson, a Minnesota lawyer and real estate developer who had acquired a 50% ownership of the company in 1980 when he invested US$600,000 in Bradley. Courneya owned the other 50%.

Among the creditors owed money by Bradley were Media Networks of New York City, IBM, Northwestern Bell Telephone, law firm McGovern, Opperman & Paquin, and Lester Electric of Nebraska. The company entered bankruptcy with an estimated US$2,500,000 of debt. Bradley Automotive did not resume operations.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bradley_Automotive